An earlier version of this article appeared on Indie Creator Explosion in May 2020.

Intro

In this article, I delve into the work of Barry Blair, a controversial figure in alternative and independent comics in the 1980s and 1990s. I want to preface this piece by saying that as a kid I was a fan of Blair’s work, particularly series like Elflord, Samurai, and Dragonring. As anyone who is familiar with his career would know, in the early 90s, Blair began creating adults-only comics when Aircel became an imprint of Malibu Graphics; basically, it was porn. While he tried to shake this reputation throughout the 1990s, Blair later went full-steam ahead into mass producing and selling original kink and fetish artwork.

When I began doing research for this article, I thought I would focus on how Barry Blair’s career needed to be remembered for much more than the porn comics or the fetish illustrations that he sold on the Internet. As I continued to do research, I found information about other controversies that I hadn’t known about. In this piece, I try to balance an appraisal of his action/adventure comics and the impact that Aircel had in its heyday in the mid to late 1980s with information about these controversies. I don’t want to feed into rumors and speculation, but I also don’t want to overlook criticisms levelled at Blair’s professional work and behavior either, particularly the criticisms that go beyond forum chatter and homophobic conjecture.

That being said, I’ll include my sources at the end of this article. If you want to dig deeper into anything that I address, then I encourage you to start there.

In the first half, I address Blair’s history as a professional artist and comic book creator from the 1970s to the late 1990s, including his self-published work through Night Wynd Graphics, the rise and fall of Aircel Comics, his resurrection of the Night Wynd imprint, his work for WaRP Graphics on various Elfquest titles, and his transition away from comics into fetish and kink illustration. After I detail this history, I address some specific controversies related to his 1989–1990 Aircel mini-series called Ripper and his relationship with Dave Cooper, which Cooper fictionalized in Dan & Larry In Don’t Do That. Finally, I conclude by raising questions about Blair’s lasting impact on comics and addressing where his work stands today.

Early Work

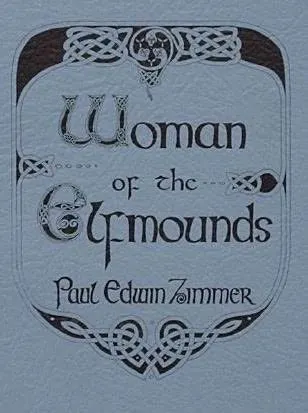

Barry Blair’s professional work as an artist began long before Aircel comics. In the mid to late 1970s, he created artwork for Triskell Press in Ottawa. Triskell Press was founded by author Charles De Lint. For Triskell, Blair created illustrations for Paul Edwin Zimmer’s chapbook Woman of the Elfmounds and for Charles R. Saunders’ magazine Dragonbane. De Lint also published a portfolio of Blair’s elf artwork in 1978. During this time, Blair also sold his artwork through his sister Sandy’s shop, Through the Looking Glass, located in Ottawa, and he created work for zines; for example, he contributed two stories about something called “The Jackal” for Roger Castleman’s publication From the Void. Some of Blair’s most memorable early work includes the opening animation sequences for the children’s television show You Can’t Do that On Television, which began airing on Ottawa’s CJOH-TV in 1979 and in the United States on Nickelodeon in 1981.

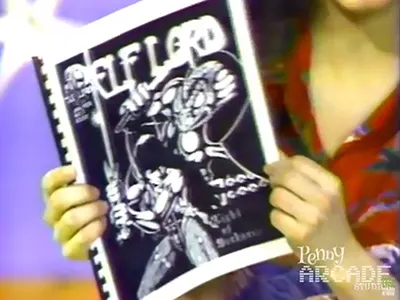

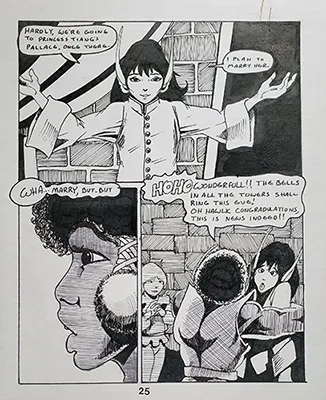

Also in the 1970s, Blair began self-publishing various comic books and selling them through local comic shops and bookstores, such as Arthur’s, which is now called Comet Comics, or the House of Speculative Fiction — both in Ottawa. At this time, Blair had been working with British television producer Roger Price to create concept artwork for a show called Star Elves. Blair had previously worked for Price on the You Can’t Do That on Television animation. Star Elves was meant to be a live-action Star Wars rip-off that featured elves, of course. When the show never got picked up, Blair used his character designs in Elflord.

He published comics under his own Night Wynd Productions imprint around the same time that Elfquest started. When Blair first saw EQ, he began corresponding with the Pinis. As he recalled, they were supportive of his work. While EQ’s success undoubtedly made more room in the comics marketplace for other fantasy books that featured elves, Blair had started Elflord years before the mid-80s black and white comics boom that Aircel comics is often associated with. That is to say, Elflord existed in one form or another before this boom and was not simply a mid-80s cash grab and an EQ rip-off as some critics have characterized it. Still, Aircel emerged during this black and white comic boom, and the company’s origin story and immediate success are well documented.

Aircel’s Origins

In the early 80s, a friend of Blair’s, Ken Campbell, owned an insulation company in Ottawa called Aircel. The company made its money because of a government funded program that subsidized the cost for homeowners to upgrade their insulation. However, money from this government program dried up around 1984, and Campbell didn’t know what to do to save his company. Blair convinced Campbell to shift the business from installing insulation to publishing comic books.

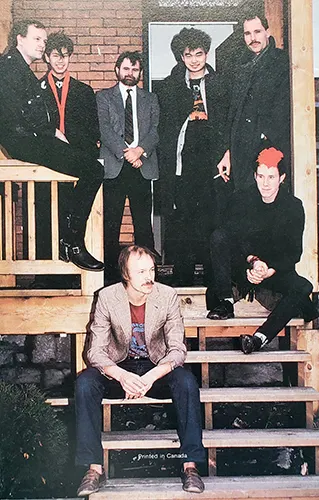

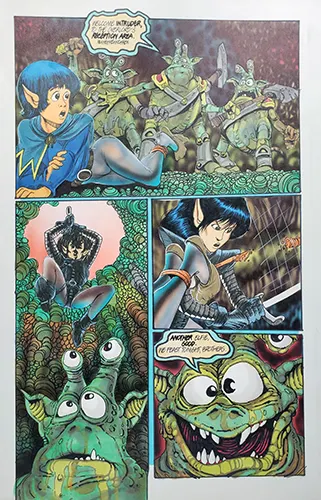

By this point Blair had already gathered a group of creators around him through his Night Wynd titles. To get Aircel off the ground, he approached the folks who had contributed to the Night Wynd publications, which included Patrick McEown, Dave Cooper, Guang Yap, Charles De Lint, Roger Camm, and Barry’s brother Bruce, among others. Once things got off the ground, Blair recruited other Ottawa writers and artists to develop Aircel titles and to work on some of the existing ones. This includes folks like Jim Sommerville, Gordon Derry, Dale Keown, Denis Beauvais, Rob Clarke, and Mike Cherbonneau. Aircel started publishing Samurai in January 1986, followed by Elflord in February 1986, and then Dragonring and Stark: Future in August of that year, and Warlock 5 in September. Elflord was the top-selling title, but Samurai and later Warlock 5 sold very well. The first few issues of Elflord and Samurai were reprinted as well as being collected into trade paperbacks that reproduced the first batch of issues for each title. The back matter of Elflord #2 (2nd printing) notes that Aircel shipped over 60,000 copies of Samurai and Elflord prior to these reprints and collections, and the company was now consistently shipping 25,000 copies of each title per month. In 1987, Aircel began publishing their major titles in color. In the early days, Blair served as Aircel’s art director while Campbell took care of the business side of things.

Serving as art director meant that Blair determined the Aircel lineup, and he managed Aircel Studios. Blair and Campbell had converted the space for the insulation business into a massive art studio, and many of Aircel’s contributors worked in this studio. In reflecting on Aircel’s atmosphere some years later, Patrick McEown likened Aircel Studios to “the animation studios I’ve been to, especially the degree of repression, sexual frustration and this really negative energy flying around” (87). Alternately, McEown describes the studio as a nerdy frat house with ”a lot of backbiting” (87) and both McEown and Dave Cooper attribute this atmosphere to Blair’s influence. (See Pat’s interview with Dave in The Comics Journal #245 for more details.)

In terms of Aircel’s content, early issues of the comics varied greatly as artists jumped from one title to another. For a while, Blair focused on Elflord, Guang Yap focused on Dragonring, and Blair, Yap, and McEown contributed to Samurai. But Aircel changed up artists from issue to issue. At one point it seems that everyone worked on every title. Editorials printed in the comics tried to clear things up periodically. One editorial claimed that a few of the artists hated doing inks and others hated doing pencils, so they tried to stick each artist with a task that they enjoyed. In a 1994 interview published in Indy: the Independent Guide #10, Blair explained that certain artists enjoyed or excelled at drawing certain things, and it got to the point where everyone would work on every book. For example, Blair would draw elves, Yap would draw machines and backgrounds, McEown would draw monsters, etc. Reading these comics as a kid, I don’t remember thinking much about the inconsistencies in the artwork because they were so frequent and because I was waiting a month between issues. Reading them nowadays in quick succession, I wonder why I didn’t care much. The artwork is not only inconsistent from issue to issue but sometimes even within an issue. A character’s hairstyle or clothing might change within a few pages, for example.

Aircel’s Operations

In 1986 and 1987, Aircel expanded rapidly, but by 1988 the company was in trouble. I am not entirely clear what the financial issues were. Some accounts state that Ken Campbell had not been paying taxes. Other accounts claim that Campbell was spending all the profits or investing money into terrible and possibly illegal business ventures. Dave Olbrich, publisher of Malibu Graphics, claims that sales for Aircel’s flagship titles had decreased dramatically, and they simply weren’t keeping the company afloat. Whatever the cause, Aircel was $35,000 in debt by 1988. In order to save Aircel, Blair made a deal with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg, who was president of Malibu Graphics at the time. In accordance with this deal, Aircel ceased functioning as an independent publisher and became an imprint of Malibu in late 1988. I’m not sure about the specifics of this deal, but Malibu covered Aircel’s debts, and the company helped Blair move from Ottawa to New York. Malibu provided Blair with a steady paycheck and dealt with immigration issues for him. The paycheck also allowed him to slowly pay off some of the debts Aircel incurred.

For the most part, Aircel’s artists and writers didn’t make the jump to Malibu. According to Olbrich, this had to do with the sales of the creators’ respective titles drying up and with that royalty payments. Many of these artists and writers went on to bigger and better things, however. In the early 90s, Denis Beauvais illustrated Aliens graphic novels for Dark Horse, Guang Yap began penciling various titles for Marvel, and by 1993 Patrick McEown was working with Matt Wagner on Grendel: Warchild for Dark Horse.

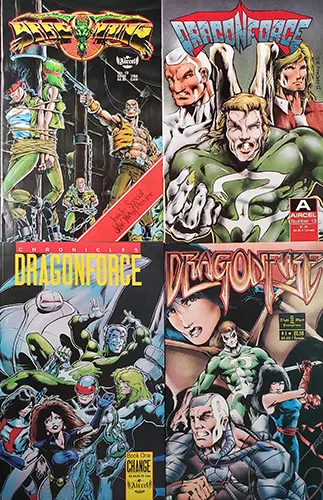

Aircel’s flagship titles also didn’t last long after the move to Malibu. By January 1989 Samurai went on hiatus. By April 1990 Elflord followed suit. Dragonring, which Dale Keown had transformed into Dragon Force and Dragon Force Chronicles, ceased publishing in January 1990 and September 1989, respectively. After Dragon Force, Keown went on to Marvel where he received great acclaim for drawing The Incredible Hulk while Peter David was writing the story. A few years later, Keown created The Pitt for Image Comics.

With their main titles on hiatus, Aircel became synonymous with adult comics like Leather and Lace, Climaxxx, Sapphire, and Vampyre’s Kiss as well as ultra-violent parodies like Gun Fury, Ripper, Body Count, and Hardkorr by 1989 and 1990. At times, Blair was writing and illustrating eight different titles a month. Between mid-1989 and the end of 1991, Malibu published over 150 comics and two stand-alone graphic novels all written and illustrated by Barry Blair. He has noted that most of Aircel’s non-adult titles shipped about 4000 copies a month while the adult titles sold 8000 copies a month; Leather and Lace was the top seller at 11,000 copies per month. The sheer volume of Blair’s work is astounding. However, the quality of this work was erratic.

In a few different interviews Blair talks about how terrible it was to create so much work that he didn’t believe in during these years. However, he did it to pay off debts. Once those debts were paid, he cut ties with Malibu and abandoned Aircel, which he had worked so hard to establish. The Comics Journal reported the departure in #144 dated September 1991. However, Aircel published its last comic by Blair, an issue of Pendragon, in Dec. of that year. Blair told folks at Malibu that he wanted to get back to Elflord and Samurai. They tried to convince him to reboot these titles as adult comics. According to Blair, Malibu was terrified about him leaving the company as his titles accounted for roughly 70% of their income. At the time, Leather and Lace was the top-selling adult comic ever. Aircel, particularly the adult titles, kept Malibu afloat. In 1992, Malibu merged with Acme Interactive in an attempt to get into the burgeoning video game market. In 1994, Malibu Interactive was acquired by Marvel. Marvel integrated some versions of popular Malibu characters into the Marvel Universe and retired Malibu and all its imprints.

After Aircel

Following his departure from Aircel, Blair relaunched Night Wynd Graphics and published a number of Elflord and Samurai mini-series from 1991 to 1993. He also resurrected a number of characters from Aircel’s non-adult titles. Additionally, Dale Keown returned to Dragon Force on Night Wynd, though the series’ title was changed to Dragon Fire.

Night Wynd published 113 comics in a little over two years — most were written and illustrated by Blair, but the venture did not succeed. Blair was simply doing too much. He had continued to produce more than five titles per month. At this point, he had been sticking to an insane production schedule for four or five years. He was burned out, and it shows in the comics. Additionally, his reputation had been severely damaged by his stint in adult comics. The Night Wynd titles weren’t porn, but the damage to Blair’s reputation and readership was done.

WaRP & Elfquest

Following Night Wynd’s failure, it is clear that Blair was searching for a lifeboat. In 1992, one arrived; he began doing work for Elfquest. At this point EQ had branched out into a number of different monthly titles written and/or drawn by various people. In 1993, the Pinis had tapped Blair for a series called Elfquest New Blood. He contributed the artwork for the series’ Forevergreen storyline, which ran in New Blood #11 to #35, from November 1993 to February 1996.

From the very beginning of his work on EQ, series creators Wendy and Richard Pini took flack for hiring Blair. Also, from the very beginning, some EQ fans who were put off by Blair’s adult-comics work and his reputation for quantity over quality. These fans began openly criticizing him in letters columns and have continued these criticisms in various online forums to this day. Such criticisms are reflected in comics journalism, for example, in an interview with Wendy and Richard Pini published in The Comics Journal (TCJ) #168 in May 1994, interviewer Andrew Craig singled out Blair by asking the Pinis what attracted them to his work.

In defending their decision to hire Blair, Wendy Pini addresses some of the criticisms simply stating that “Barry Blair is probably one of the most misunderstood people in comics. He has dealt with subject matter throughout his career that has made a lot of people uncomfortable” (91).

Not content to let the line of questioning drop, Craig raises another question about Blair later in the interview. Craig asks the Pinis, “What would you do if, for example, Barry wanted to do something really bizarre?” (96). When asked to clarify his question, Craig continues, “Let’s say one of the young guys is gay or something.” Craig’s question gets at an underlying criticism of Blair’s adult comics work: he depicted young-looking male characters as sexual on the one hand and as explicitly gay on the other. In response Wendy simply states, “I’m going to come right out and say that every single blasted one of our characters is bisexual.” I applaud Wendy Pini for her response and for defending Blair against some common criticisms of his work. I also bristle at the TCJ writer for being so prude considering the edgy nature of the work that TCJ has lauded since its inception.

Blair’s depiction of “young boys in tights” earned him a tremendous amount of criticism following his stint creating adult comics for Aircel/Malibu. Still today, anonymous posters in online forums label Blair as a homosexual pedophile. I don’t know if Blair was gay. I haven’t seen any information stating that he ever addressed his sexuality publicly. However, I can say that the depiction of gay men as pedophiles is a despicable trope that homophobes have used to deny LGBTQ+ people rights, and I believe that some of the ire aimed at Blair reflects this bigotry.

In defending their decision to work with Blair, Wendy Pini also addresses the uneven quality of his artwork at Aircel; both Wendy and Richard argue that if he would focus on fewer titles, his work would improve. I tend to agree. Unfortunately, Blair would never focus on fewer titles. He would spend the remainder of the 90s working on innumerable projects for myriad publishers all at the same time.

In trying to keep his own titles alive, Blair began contributing an Elflord back-up story in Drew Hayes’ Poison Elves series in 1994. This back-up story was intended to be ongoing; however, only one installment saw print in Poison Elves vol. 1, #16. As the rumor goes, Poison Elves’ move from Hayes’ own imprint, Mulehide Graphics, to Sirius Entertainment did not include space for Blair’s back-up story.

Following the brief stint in Poison Elves, Blair published one-off graphic novels for Elflord and Samurai with Mad Monkey Press in 1996. Also in 1996, Blair worked with artist Delfin Barral on another Elfquest title, a six-issue mini-series called Two Spear. Additionally, Blair contributed the artwork for Fire-eye, an ongoing EQ story that ran from June 1996 to February 1998. Installments of Fire-eye appeared intermittently in a monthly EQ anthology series. Finally, Elflord and Samurai returned as mini-series published by WaRP Graphics in 1997.

While Blair created these works for WaRP and Mad Monkey, he also had work published by Sirius Entertainment. In 1996, Sirius published a ten-issue run of a series called Demongate under the name Bao Lin Hum. I am not sure why Blair published the series under a pseudonym. I wonder if his contract for WaRP precluded him from working on series for other publishers or if Sirius didn’t want Blair’s name affecting their reputation. In any case, Sirius also resurrected Warlock 5 for a 4-issue mini-series in 1998. Also in 1998, Davdez Arts and Peregrine Entertainment published a few of Blair’s mini-series and graphic novels, including Legend of Elflord, Lynx: An Elflord Tale, Demon Hunter, and Dark Island.

Many of these Elflord titles and iterations don’t relate to one another, neither in the story or in the style of artwork. It is unclear to me if moving from one publisher to another and ignoring continuity across different iterations of Elflord and Samurai was a choice that Blair made deliberately or out of desperation — maybe both. In either case, it seems that for Blair financial decisions trumped all, which is of course understandable. Living off the money one makes by publishing with small presses seems a bit insane, but at this point he had been in the comics industry for the past 15 years. What else could he do in his mid-40s? Changing careers is never easy.

Returning to Adult Comics and Selling Artwork Online

While it is hard for me to pinpoint exact dates as so much information from the Internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s has simply disappeared, it seems that Blair moved back toward adult illustration during the late 1990s. (The “Way Back Machine” is only useful if you know which way you want to go, that is to say if you have URLs saved.) Alongside publishing adult comics like Sapphire and pin up books like Nymphettes with NBM and SQP, respectively, Blair began selling original fetish and kink artwork online under the moniker “The Blair/Walbridge Project.”

This artwork became its own cottage industry, and by the mid-2000s it was just about the only place to find Blair’s art. However, not all of it was pornographic or cheesecake. In a video shot in 2004 that documents how the Blair/Walbridge Project worked, Blair states that he was creating and selling about 25 original pieces every week. Blair and his partner Colin Walbridge handled the artwork, and Santos Aleman dealt with orders via eBay.

In 2009, the trio announced Studio RealmWalkers, which offered affordable artwork to online RPGers. Blair would draw illustrations of gamers’ characters on commission. This move appears to be Blair’s last attempt to pivot away from focusing on fetish illustrations. Shortly after the studio website launched, Barry Blair died of an aneurysm on January 3, 2010. He sought medical attention before his death, but the symptoms were misdiagnosed as an ear infection. Barry Blair was 54 when he died. The comics press was almost entirely silent about Blair’s death. A few comic and pop culture websites, like Bleeding Cool and Heidi McDonald’s The Beat, printed short blurbs about Blair, and Tom Spurgeon promised an article appraising Blair’s work and impact, but Spurgeon’s article never materialized.

Since his death ten years ago, Blair’s original artwork has been continuously available via eBay. The amount of work that he created prior to his death is massive. Much of it is adult fetish illustration. But, you can find cover art or pages from issues of Elflord, Samurai, and various other titles, even artwork from these titles that was created for the 1970s Night Wynd comics. Personally, I own a small collection of his work from Elflord that I purchased on eBay.

The Controversies

Blair’s career was not without controversy. These controversies stem from a 1989/1990 mini-series published by Aircel called Ripper; Blair’s adult comics and fetish illustrations; and his friendship, for want of another term, with Dave Cooper when Cooper was a teenager. In this section I describe these controversies.

Ripper

In February 1990, The Comics Journal #134 included two columns indicting the first two issues of Blair’s mini-series Ripper for racist depictions of Black people. The first column, Robert Boyd’s “Racist Murder as Entertainment,” describes how 9 of the 12 Black characters depicted in the premiere issue are “drug addicts, drug dealers, rapists, and/or murderers” and that Blair drew these characters in a long-standing racist tradition with “popping eyes and subcontinent-sized lips” (3). Furthermore, Boyd notes that the white titular character in the series spends much of the first two issues murdering Black people. Boyd argued that the mini-series amounted to little more than a blood-soaked, racist fantasy. Gary Groth followed up Boyd’s column with one of his own called “Spin Controlling Racist Comics.” In his column, Groth takes both Blair and Malibu Graphics to task for Ripper. Groth lambasts Dave Olbrich, Malibu’s publisher, for advancing the argument that Blair was depicting the state of mind of a racist character and not his own political agenda. Both Boyd and Groth called for boycotting Blair’s comics and Malibu writ large. Following these columns, Blair offered an apology in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, and Dave Olbrich maintained that the series was about racism rather than being racist. In continuing the mini-series, Blair changed the hero, killing off the white Ripper and replacing him with a Black Ripper. While the mini-series was only meant to be four issues long, Blair extended the series to six issues; I assume that he added two issues in order to make changes that may not have been part of the original storyline. It is unclear what if any effect the controversy surrounding Ripper had on Blair’s career. Aside from the columns in The Comics Journal and Blair’s apology in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, I see no further references to the series.

Adult Comics and Fetish Illustrations

Blair’s adult comic book titles published by Aircel/Malibu, such as Leather and Lace and Sapphire, reflect some of the worst straight-boy power fantasy clichés that comic books from the 1980s and 1990s had to offer: they featured over-sexed, big-breasted heroines with tiny waists who brandish guns and wield swords. The plots are negligible. Often times, these heroines spend their time fucking or avoiding torture and rape. These comics also featured two kinds of male characters: creepy looking old men who spent much of their time trying, but often failing, to molest the heroines and who succeeded in molesting the other male characters — mostly young-looking boys who served as the heroines’ sidekicks and house boys. These boys only existed to satisfy the heroine’s needs, the old men’s torture fantasies, and occasionally one another. Blair’s adult comics might stand out from others of the time for one reason: virtually every character was bisexual, or, maybe more accurately, pansexual. Considering that this was the late 1980s and gay men in particular were still being vilified by mainstream media in the midst of the AIDS crisis, making the characters pansexual was a daring move. Still, it’s a move that folds neatly into comic book clichés as the highpoint of an issue’s storyline often occurred when the heroines diddled one another.

For the most part, these adult titles ended when Blair left Aircel in 1991. However — as I noted previously, when his return to action/adventure comic book publishing fizzled in the late 1990s, Blair turned to fetish illustration in order to support himself. I’ve seen little mention of these illustrations in the comics press, but Blair’s name would forever be synonymous with the adult work that he created. Detractors claim that they object to the fact that many of his male characters appeared to be very young. Still, it’s hard to separate these characters from their sexualities, that is to say from the fact that they swung every which way, and criticisms often take issue with the characters’ sexuality as well as their apparent age.

Dave Cooper’s Dan & Larry In Don’t Do That

Finally, Dave Cooper raises questions about how Barry Blair treated the creators that he managed at Night Wynd and Aircel from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. Some of these creators, including Cooper and Patrick McEown, were young teenagers when they began working with and for Blair. Cooper provides a fictionalized account of his experiences in Dan & Larry in Don’t Do That. Initially, Dark Horse Presents printed the story in serialized form beginning in 1998. Fantagraphics later collected the story in its entirety as a graphic novel in 2001.

The story focuses on two characters Dan, a 12-year-old duck, and Larry, an older, mutated, robot character who sweats a lot. When we meet Dan and Larry they are wandering through a forest. We see an uneasy tension between the two. Dan is always on edge, and Larry behaves erratically, yelling at Dan one moment and dry humping him the next. When Dan and Larry part ways, we learn more about Dan’s life: people think he’s older than he actually is; kids his age treat him like crap; he inks Larry’s comic, Gnomes in Dimension 12; he questions his sexuality; and his parents are detached from all of it. The story concludes with a scene where Larry goads Dan into jerking him through a leotard, after which Larry trips and falls onto his own sword and chops the top of his head off. To put it mildly, the depiction is dark. Dan is being manipulated by an older man: the only substantive relationship Dan has is marked by an imbalance of power.

In The Comics Journal #245, Patrick McEown interviews Cooper about Dan & Larry. Early in the interview, McEown and Cooper describe how Blair “seemed like a big brother character at the time” (81). McEown continues, “I think, because of his comics and rumors of his reputation, people tend to assume it could only have been a predatory thing. But it was actually really quite friendly. I think he was genuinely interested and just more comfortable in that situation” (81). The situation that McEown refers to is working with younger people. Cooper goes on to say that Dan & Larry should not be interpreted literally: “Like a lot of my fiction, I’m drawing on things that really happened, [but…] distorting everything for the sake of a good story” (82). He also states that Larry did not rape Dan, but “thing[s …] got a lot weirder than it should have. I guess a lot of people read it as just straight-out rape. That completely changes the whole feel of the book. It should be read as an awkward, weird thing that almost went too far — and didn’t” (83–84).

I’m not entirely sure what to think about Dan & Larry or what it says about Barry Blair. Clearly, whatever transpired had a dark and lasting impact on Cooper. Clearly, it displays an imbalance of power and Blair’s manipulation of Cooper. Still, Cooper has stated multiple times that readers should not take the events of the story literally.

Blair’s Lasting Impact

In concluding this article, I am unsure of how to characterize Barry Blair’s lasting impact. The part of me that enjoyed his early Aircel comics wants to acknowledge that for much of his career, he struggled to make ends meet. Despite a short stint in independent comics’ halcyon days in the mid 80s, he existed on the periphery of the comic book industry and later at its extreme fringes. Part of me wants to make the case that his artwork shows flashes of brilliance throughout his career, particularly in his self-published early work and in the first dozen or so issues of Elflord and Samurai for Aircel. That same part of me wants to acknowledge that Aircel played an important role in the black and white comics boom. Rereading through the first dozen or so issues of Elflord, Samurai, and Dragonring, I see that some great artwork and writing got bogged down by the demands of monthly publication and the desire to push out a number of titles at the same time without a reliable stable of artists. This pace means that many Aircel comics incorporated pop culture homages and, at times, tired tropes. In some sense, these tropes weren’t as cliché in 1986 as they became later on. Still, they were trite, and some comics historians and fans associate Aircel comics with sloppy, cliched work rather than lauding any of the unique contributions that the publisher’s series contributed to the field. For example, Aircel comics featured a number of Asian and queer characters at a time when mainstream American comics were dominated by white, heterosexual characters. Additionally, Aircel offered readers many different flavors of adventure comics and very few superheroes. Many of these genres were jammed together in interesting and unusual combinations. For example, Elflord shifts from a European, Tolkien-inspired approach to elf mythos to an Asian influenced approach over the course of its history, and Samurai mixes trappings of martial arts films with punk rock, the occult, and science fiction. This focus of fantasy, punk rock, the occult, and sci-fi offered readers who were tired of spandex and capes a refuge. Furthermore, Aircel gave many amazing artists their start in the comics industry, from Dale Keown and Denis Beauvais to Dave Cooper and Patrick McEown. I question if any of these artists would have gone on to have the careers that they have had if not for Aircel and Blair’s work as art director during the company’s early years.

Another part of me cannot reconcile my love of Aircel and Blair’s work with some of the controversies. This part of me acknowledges that Blair sounds abusive — whether deliberately or not — towards his employees during Aircel’s early days: while Dave Cooper goes out of his way to say that Blair did not sexually abuse him, Cooper hints at how Blair mistreated him in other, psychologically damaging, ways. Furthermore, Blair’s depictions of many, though not all, of the Black characters in Ripper are racist. Reading through the mini-series, one can see how Blair shifted its focus in order to address critics and save face. While this shift was significant, it doesn’t absolve Blair for the first two issues. Unfortunately, I do not have access to the apology that he wrote about Ripper in the Comics Buyer’s Guide. While an apology would not have changed these depictions, I am curious how he addressed being called out by contributors to The Comics Journal.

In the end, this is not an easy tribute, nor is it an indictment of a human being. I didn’t know Barry Blair at all, and I never met him. My goal here is not to judge him. My goal is to attempt to document the complex issues surrounding his career, and in so doing, I try to contextualize his professional successes as well as his shortcomings; appraising his career means grappling with his confusing professional decisions; it also means calling out the homophobia that he experienced as well as criticizing the cliched depiction of women and young-looking male characters in his fetish art; it means condemning the racist content in early issues of Ripper and how he treated Dave Cooper and others; it also means that there are things worth knowing about and learning from his career.

In researching and preparing this piece, I feel like something that was very important to me as a kid has shifted. The remnants of fannish devotion have been replaced by more complex feelings about Barry Blair’s work. No one wants to spend hours and hours researching someone whose work they adored as a kid only to find that their hero’s professional history is less than glowing. Maybe, beneath it all, the lesson here is that while comic creators may depict heroes, they are just regular people. They have issues, they fuck up, and they all need to put food on the table however they are able to do that. Sometimes that means they push out eight comics a month, even as the art and stories in those comics suffers because of that insane pace. Sometimes that means they sell cheesy fetish art on eBay. In the end, Barry Blair left a treasure trove of comics to explore. In the end, I will always remember Hawk Erickson, Windblade Greensleeve, and Toshiro Kimura fondly.

Coda

In 2015, Kansas City, MO-based Outland Entertainment announced The Barry Blair Library. As part of this project, Outland published a number of short articles about Blair’s work on their website. These articles were written by comics journalist Christopher Helton, formerly of Bleeding Cool and EN World. Outland also made several issues of various Aircel and Night Wynd series available on Comixology, including foundational titles like Elflord, Samurai, and Dragonring as well as lesser known series like Blitz, Blood N Guts, Body Count, Children of the Night, Dark Island, Demon Hunter, Foxfire, and Gun Fury.

This move toward making Blair’s oeuvre available digitally followed two successful Kickstarter campaigns. With these campaigns, Outland intended to reboot Elflord (as Elflord Reborn) in 2015 and Warlock 5 in 2017. Both campaigns succeeded; Elflord Reborn raised $8287, and Warlock 5 raised $15,215. Written by Mat Nastos and illustrated by Tony Vassallo, the single issue of Elflord Reborn was well-executed, bears little resemblance to Blair’s Elflord. Outland released their Warlock 5 graphic novel in April 2019. It is unclear whether or not that series will continue although the story reads as the beginning of something new.

More recently, Outland completed two more Kickstarter campaigns for Aircel titles: a 2020 campaign for a Warlock 5 Omnibus, which featured two unpublished issues of the comic created by artist Denis Beauvais and writer Gordon Derry, which raised $10,679; and a 2021 campaign to reboot Dragonring, which raised $7,730. The Warlock 5 Omnibus raises questions about another controversy that I have not touched on in the main text of this article, namely who owned the intellectual property. When Beauvais and Derry parted ways with Aircel, the creators fought to retain control of the title, and Blair contended that he created the property. While Warlock 5 continued as an Aircel title for another 16 issues, the series bore little resemblance to the Beauvais/Derry version. Blair later changed the title to Warlocks and published another 15 issues of the comic with Aircel. Later, he published 4 issues of a rebooted Warlock 5 with Sirius Entertainment.

Finally, in November 2020, Outland added a number of comic covers to the Barry Blair Library and some information about each title. These covers span most of his career, including comics he made for Aircel and his early 90s Night Wynd imprint as well as his work for WaRP Graphics, Mad Monkey Press, Davdez Arts, and Sirius Entertainment. While many of these titles are not yet available digitally, maybe there is hope that they will be available one day. The covers included represent the lion’s share of Blair’s work, excluding his adult comics, such as Leather and Lace and Sapphire and his earliest, self-published comics.

Works Consulted

Betz, John. (2006?). The Blair/Walbridge Project. Sock Pirate Films. DVD.

Blair, Barry & Chan, Colin. (2008). Realm Walkers.

Boyd, Robert. (1990). Racist murder as entertainment. The Comics Journal, 134, 3–4.

Groth, Gary. (1990). Spin controlling racist comics. The Comics Journal, 134, 5–6.

Helton, Christopher. (2015, June 22). Elflord: Past, present, & future. Outland Entertainment.

Helton, Christopher. (2015, June 19). Warlock 5. Outland Entertainment.

Helton, Christopher. (2015, June 15). Barry Blair’s Samurai. Outland Entertainment.

Helton, Christopher. (2015, June 8). Barry Blair: What to read first. Outland Entertainment.

Helton, Christopher. (2015, May 29). Barry Blair 101. Outland Entertainment.

Johnston, Rich. (2010, Jan. 3). Founder of Aircel Comics, Barry Blair, dies. Bleeding Cool.

Kouns, Cat. (1994). Interview: Barry Blair. Indy: The Independent Guide, 10, 40–41.

McDonald, Joe. (1995, Dec. 10). The Podium interview with Barry Blair. The Podium.

McEown, Patrick. Interview: Dave Cooper. The Comics Journal, 245, 76–105.

Muir, Adrian. (2010) The art of Barry Blair & Colin Walbridge.

Munn, Bryan. (2010, Jan. 5). Barry Blair: 1959–2010. Sequential Pulp.

Nastos, Mat. (2010). Studio Realm Walkers.

(n.d.) Aircel Comics. Malibu Comics Wiki.

Olbrich, Dave. (2008, Dec. 26). Ask the DWP: Dale Keown. Funny Book Fanatic.

Outland Entertainment. (5 Oct. 2021). Dragonring by Collen Bunn and Shannon Potratz. Kickstarter.

Outland Entertainment. (2 June 2020). Warlock 5 Omnibus by Den Beauvais & Gordon Derry. Kickstarter.

Outland Entertainment. (2017, Apr. 6). Warlock 5: Comic written by Cullen Bunn & Jimmy Z. Kickstarter.

Outland Entertainment. (2015, June 16). Elflord Reborn. Kickstarter.

Staff. (n.d.). The Barry Blair Library. Outland Entertainment.

Staff. (2017, April 25). Warlock 5 is coming to Kickstarter on April 26. Outland Entertainment.

Staff. (2015, June 15). Elflord Reborn coming to Kickstarter tomorrow. Outland Entertainment.

Staff. (2015, Mar. 3). Outland Entertainment brings a collection of Barry Blair’s comics to the digital age. Outland Entertainment.

Staff. (2010, Jan. 5). RIP Barry Blair. The Beat.

Staff. (1993). Barry Blair joins WaRP Graphics. The Comics Journal, 168, 32.

Staff. (1991). Barry Blair ends Malibu contract, starts own firm. The Comics Journal, 144, 7.

Verstappen, Nicolas. (2008, Aug.). Dave Cooper. du9: l’autre bande dessinée.

Wulff, Ariel. (1998). Artist/writer profile: Barry Blair. Sendings, 5.