This article was written by Michael Crisman and originally published in 2018 at Peakd as part of his Michael’s Longbox series. It’s republished here with permission. — KF.

I’ll be the first to admit that as a dude so white he inspired a Cool Whip diss track, I’m the wrong person to write this article. Despite that, I’m moving forward on it because nobody else has done so. My hope is that I’ll engender curiosity and someone else, someone more suited to the task, who understands what it means to grow up as a young man of color in the United States, can take this and run with it.

Upfront, I want to make it clear: I’m no sociologist, no anthropologist, no expert in race relations, and white enough to be mistaken for mayonnaise if I’m standing in the wrong aisle of the supermarket. I’m going to do the best with the skills I have, using the language of the day and the words of the creators themselves from the early 90’s. But I have not lived the life, and I don’t dare presume to understand anything of African-American culture. If I make mistakes, please know these errors are my own and by all means correct me. If I offend, if I use incorrect terminology, or if I bring M.C. Hammer to a Jay-Z battle, know it’s not intentional and correct me. But please, if nothing else, forgive me for being the one who writes this story. It shouldn’t be me. I’m doing it because no one else has yet.

This is a story about a dream.

Diversity in pop culture is a hot topic. Black Panther, a feature film about the head of a fictional African civilization who originated as a backup player in the Fantastic Four universe, is one of the top-grossing films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. A mixed-race teenager of Afro-Latino descent is swinging his way through his own animated series and an animated film as well as a top-selling comic. Michael B. Jordan stepped through the ropes as Adonis Creed to challenge the son of the man who killed Adonis’s father in the second film of a Rocky spin-off. Idris Elba has not only been voted the Sexiest Man Alive, but there’s a growing desire in the fan community to see him cast as the next incarnation of James Bond. The day where heroes with skin tones best represented with shades of umber and sienna are stars in control of their own destinies and attract audiences of all ethnicities including people with an undeniably European descent like myself, has arrived.

This may feel very new, but for men like Nabile Hage, Roger Barnes, and Roosevelt Pitt, it must seem a long-time coming. That’s because these men saw this future and attempted to drag it into their present all the way back in 1993, when they rocked the comic book boat by taking a page from the likes of Defiant, Malibu, and Image and created their own imprint: ANIA.

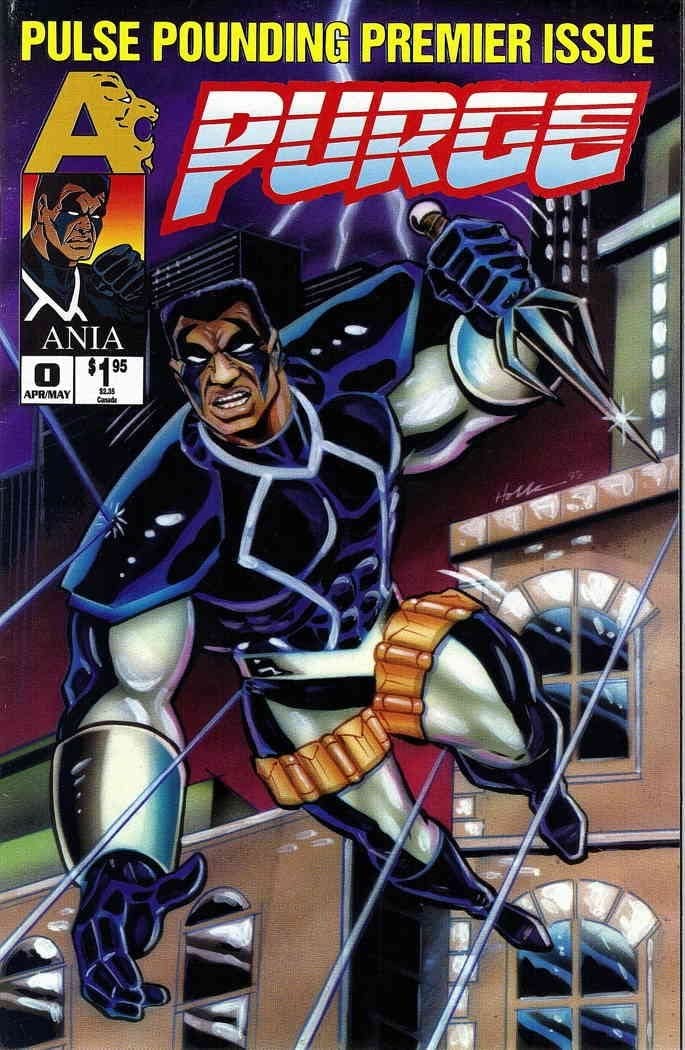

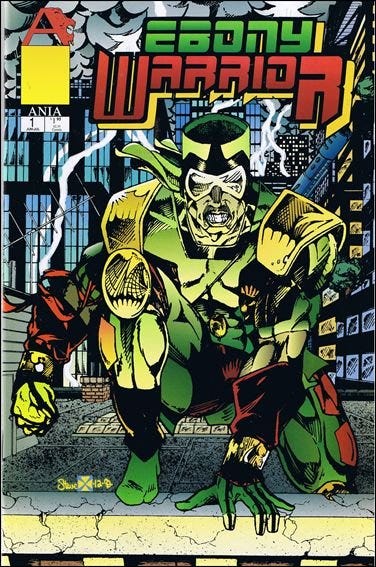

ANIA is taken from a Swahili word meaning “defend” or “fight for”, and it wasn’t one organization but rather a combination of six separate African-American-owned publishing arms. ACB Comics, Hype Comics, Up Comics, Dark Zulu Lies, Omega 7, and Africa Rising all joined forces under the ANIA banner with the intention of moving their stories, featuring Afrocentric heroes and mythology, out of niche stores catering to Black interests and into mainstream comic shops. While the dream to break into the $500 million-$700 million comic book market might have seemed crazy, the results achieved must have seemed even moreso: for a brief period of time, ANIA was the 16th-largest publisher of comic books in the entire world. Now granted, that’s not exactly Marvel, or Image, or even Dark Horse, but for a comparatively small conglomerate of content producers aiming at what even today would be a niche segment of the market, that’s astounding.

So, why ANIA? After all, black heroes and villains already existed within the pages of the two largest comic companies. Marvel had the likes of Storm, Luke Cage, and the aforementioned Black Panther among others in their repertoire; DC had the Superman-banner-carrying Steel, Justice League member Bloodwynd, and power-armored Hardware in their cast of ethnic characters. Hardware, along with fellow heavyweight Icon, were originally part of Milestone Media, an imprint of DC created specifically to publish titles catering to African-American audiences, primarily written and drawn by African-American creators.

What did the people behind ANIA see as their role to play in the comic book world?

Nabile Hage put it this way:

The predominant culture in comics was a white perspective that was evident in both white superheroes and the so-called black superheroes. If they were black, (the characters) were ethnically incorrect-in appearance, speech and mannerisms. They were developed from a white perspective.

The thinking at the time, by Hage and others, was that most creators were essentially ‘blackwashing’ (for lack of a better term) the occasional character in their books. While the skin tone was correct, the way they carried themselves on the page and talked with their fellow heroes and villains was not. That’s not to say the creators’ hearts weren’t in the right place, but the end result was something the people behind ANIA felt no young black man or woman could look to for real inspiration. Even a character like Storm, who was worshiped as something of a goddess in her native Kenya with her ability to control weather, was brought to the United States under the tutelage of Professor Xavier.

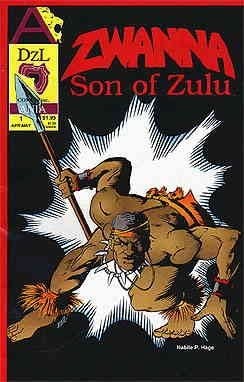

ANIA set out to change that perspective, with characters like Purge, who fought against racist elements in his city, and Heru, Son of Ausar who combined elements of African religious traditions and symbolism with the 90’s era depiction of modern African leaders and role models. Not all of the stories were set in the United States either. Heru took place in Kemet, the African name for Egypt in days of old, for instance. Zwanna: Son of Zulu focused on an African prince who left home to study abroad in the US, but then returned to Africa to help defend his kingdom against the forces looking to usurp his ancestral right. Ebony Warrior fights bad guys as you might expect, but is something of a bookworm and amateur historian in his spare time. The heroes of ANIA’s books fought not just criminals, but also tackled topics like AIDS/HIV, racism, gun culture, and violence within the black community.

As ANIA president Eric Griffin related, modern-day interpretations of black characters in comic books were remarkably narrow. “Most of them are hoodlums and thugs without any direction,” he stated in an interview with the Seattle Times. They weren’t role-models. His goal, and the goal of all the companies beneath ANIA’s banner, was “to instill in their young readers a sense of hope and a belief in their self-worth.”

So, why hadn’t I heard of ANIA before?

Well, to be honest, it seems like they didn’t last very long. The actual timeline for the company is unclear to me from the research that I’ve done, but it appears most of the titles had very short runs. Whether this was due to a sudden drop in sales, a difficulty with creators hitting their strides, ANIA being simply too ahead of their time, or a mixture of all of the above, I wasn’t able to determine. There is precious little information about ANIA today in modern media. I myself only learned about them when I sat down to flip through a back issue of a comic magazine, and discovered the announcement of the company’s formation in a three-paragraph sidebar (Wizard #18, page 8 if you’re looking to dig into your own archives). From all I’ve been able to gather, it looks like they managed to last a few months and then just faded into obscurity. Most titles didn’t sell past a single issue in the direct market. ANIA, as the majority of new business ventures do, ultimately wound up a failure.

I don’t know what it is about this particular imprint that got me interested. There are plenty of small-time publishers and studios I’ve never heard of, even with thirty-some years in the hobby. I never collected their titles, I don’t own any of their books, and I’m completely unfamiliar with their characters and creations beyond what I’ve related here. But something about this publisher just struck me as worthy of remembrance.

ANIA had a goal, and it was a worthwhile goal. From the limited number of interviews I’ve been able to track down online and watch or read, these were creators interested in touching lives, in delivering something into the hands of their younger peers that they never had but would have loved at that age. ANIA, first and foremost, screams out as not an angry rejoinder to the predominantly white culture of 90s comics, but as a heartfelt labor of love by creators motivated by a drive purer than simple profit.

They wanted a new heart, a beating heart, an African heart, pounding away in the breasts of their creations. They wanted a heart that could speak to their children in a culture and manner denied them by the mainstream. It was a cry for truth, that their stories mattered, that the problems they faced were just as real as those faced by their white neighbors and classmates and co-workers, that the stories they had to tell were just as profound.

In 1992, Nabile Hage donned a Zulu costume and climbed to the third floor of the Georgia State Capitol building. Standing on a ledge, outside a window, he hung a yellow banner with the words “Dark Zulu Lies” on the facade, and hurled copies of Zwanna, Son of Zulu to passersby on the street below to promote both the comic and his company. He was ultimately arrested and held for several hours before being released without either the city or the state pressing charges. You might think a person deciding to become a real-life Spider-Man for a couple of hours for a marketing stunt must be insane, but in interviews, Hage comes off as anything but crazy. Instead, his testimony is that of a man unable to make himself heard above the ordinary noise and bustle, but who believes in his story and his message so much that he’s willing to go to extraordinary lengths just for a chance at having someone else hear.

Well, here we are twenty-six years later, and I’m just now hearing his voice. It’s too late for ANIA, and it appears most of the creators have moved on to other things, though some are keeping the flame alive. Roosevelt Pitt, for instance, attempted an Indiegogo campaign to resurrect the character Purge three years ago. Alas, it raised only 10% of its funding goal.

Some people still heard the voice. I hope that if I’m not the only one who hears, if there are others who know more, and who can shed further light on this subject, that they’ll be tempted to do so by this post. I’ll continue combing back-issues of Hero, Wizard, and the like to see what else, if anything, I can uncover about these creators and this publishing venture. If I learn more, I’ll share it here.

In the meantime, please enjoy these two YouTube videos from Roosevelt Pitt’s own YouTube page that explore the unsung heroes of 1993’s Black Comic Book movement:

Black Panther, Adonis Creed, Blade, Cyborg, Storm, John Stewart’s Green Lantern, Nubia, Miles Morales, Vixen, Luke Cage, and more are still blazing trails as heroes and heroines of color, hopefully inspiring young people of color, to be the best they can be against a world that wants nothing more than to grind them down. I would like to think ANIA cut away some of the brush overgrowing that path twenty-five years prior, and I’d like to think it shouldn’t be up to a guy white enough to shame cottage cheese to start the ball rolling on the discussion of an Afrocentric comics publisher. That kind of passion deserves a wider audience, and a much more diverse chorus of interested voices. If these ramblings help make that happen, then it’s been my honor to set up the first domino.

More Information

A 2019 episode of the Rolled Spine podcast took a more critical view of Ania.

Gone and Forgotten provides another critical take on the books