Ahhh, the Golden Age of Comics. When heroes were unambiguously good, and the villains were unambiguously evil. An era before all the sex and violence and politics and the cash grabs and the gimmicks, when comics were just wholesome fun.

Well, not quite. The Golden Age featured darker content than one might think. The goldenest part of the Golden Age, from the first appearance of Superman in 1938 to the end of World War II in 1945, was before the establishment of the Comics Code Authority. That allowed for much darker, more disturbing stories than publishers could get away with in the Silver Age. It also helped lead to a crackdown that nearly killed the industry.

No code

The Golden Age of Comic Books was also the era of the Hayes Code in film. The lack of a similar code for comics meant that comics could actually get away with things that movies couldn’t. And while the assumption was then, as ever, that comic books were for kids, Wonder Woman co-creator William Moulton Marston claimed in 1943 that around half of comic book readers were adults. He does not cite a source, but I would guess that many of those adult readers were in the US military, as it’s been widely reported that comic books were often included in care packages sent to soldiers overseas during World War II.

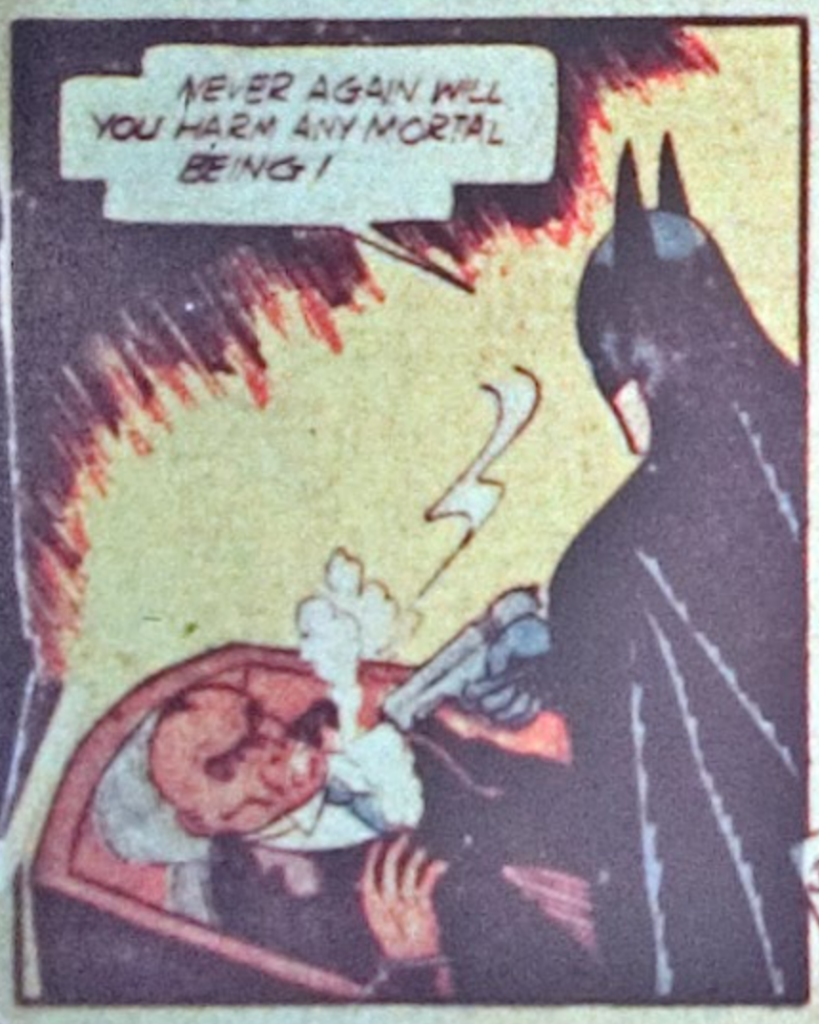

Today’s Batman doesn’t carry a gun and has a strict code against killing. But it wasn’t always so. He carried a gun in some of his early appearances. In Detective Comics issue 31, he shot and killed a vampire with a silver bullet. Maybe that doesn’t count as murder, but there were many in the Golden Age who unambiguously killed their enemies. Here’s writer and researcher Jess Nevins on “killer vigilantes” in the Golden Age:

There are a number of Golden Age superheroes who began as killer vigilantes and then changed their murderous ways and never killed again. […] And there are also superheroes who killed their opponents, but in a wartime setting and when their opponents were Axis agents and soldiers, so that the superheroes technically aren’t so much vigilantes as they are patriotic warriors or soldiers. Captain America is among those superheroes, as he infamously killed a million Japanese soldiers.

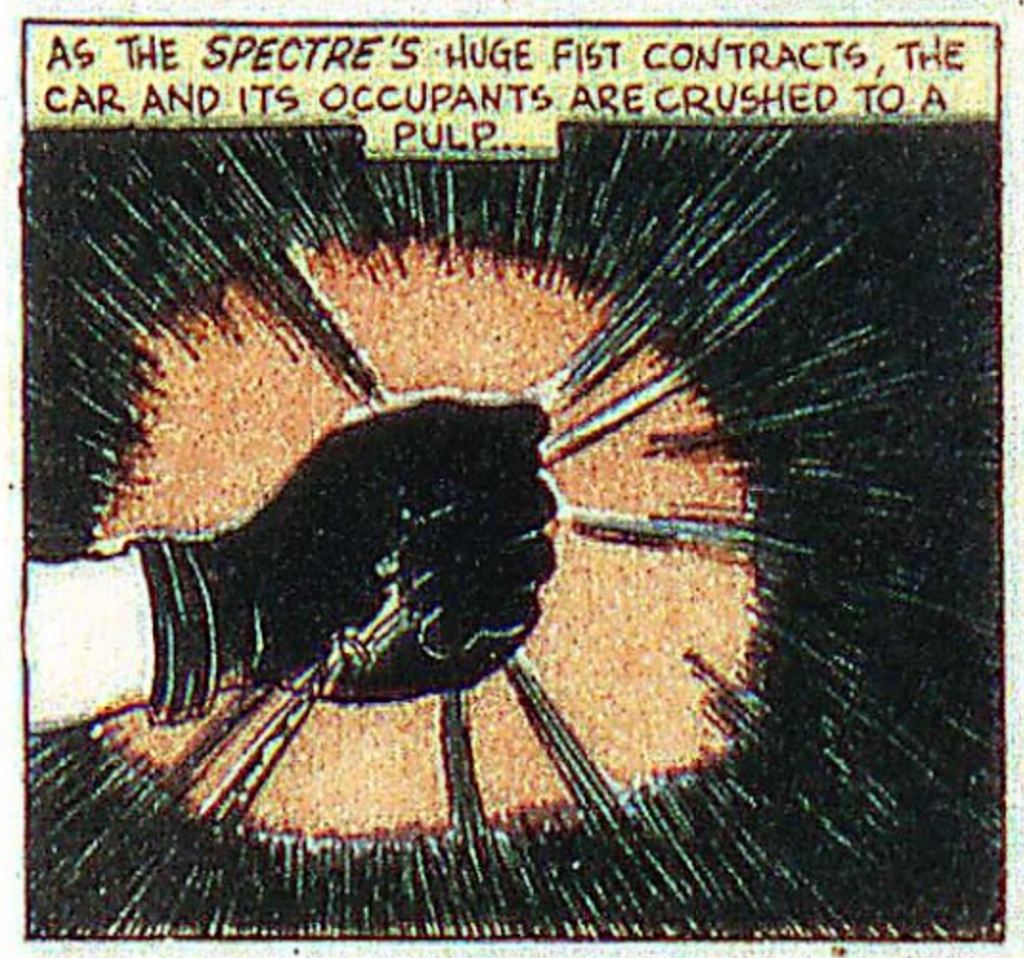

Batman’s foes got off easy compared to those who crossed The Spectre. In his second appearance, in More Fun Comics issue 53, he reduced an enemy to a skeleton, exclaiming “DIE!” as he killed him. In an infamous sequence from More Fun Comics issue 56, The Spectre grew to a gigantic size and crushed a car containing a pair of hit men “to a pulp,” ignoring their cries for mercy.

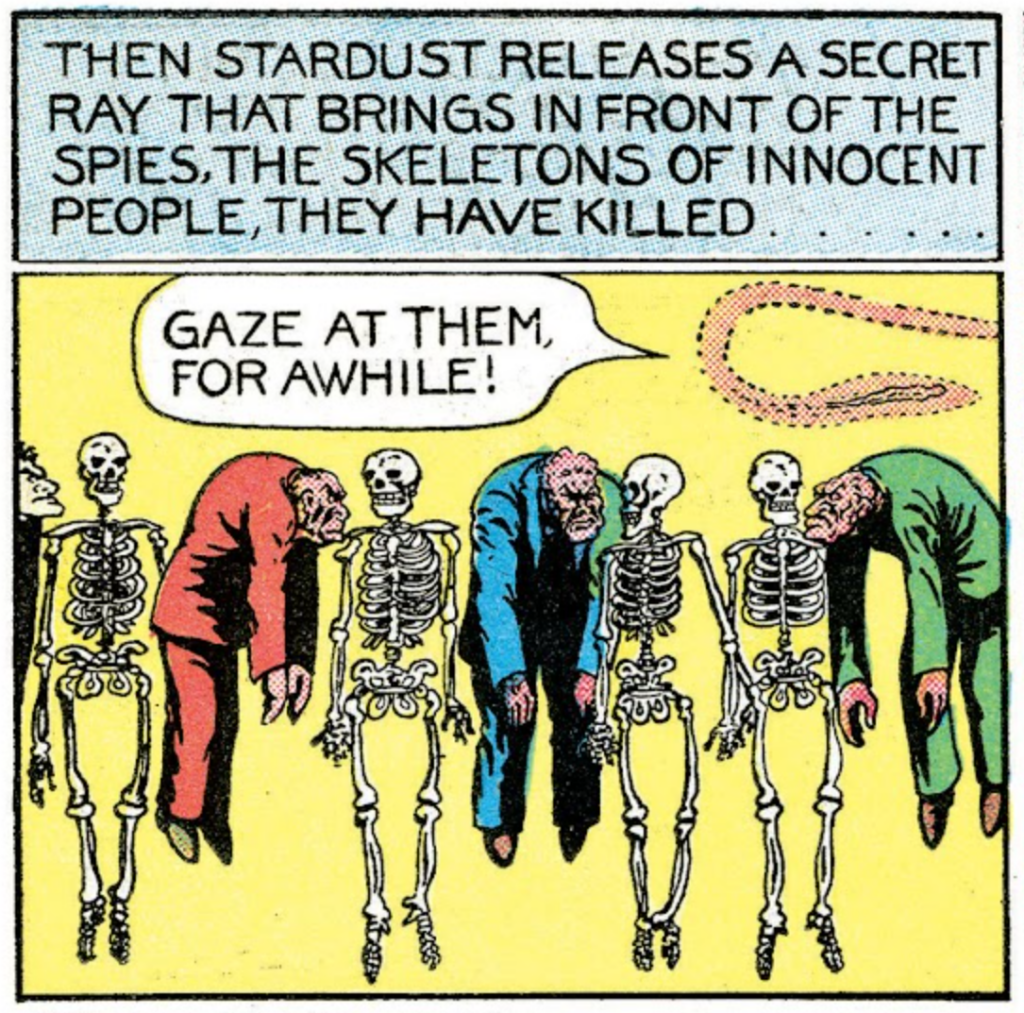

Meanwhile, Fletcher Hanks’s characters Fantomah (the first superpowered woman superhero in comic books) and Stardust the Super Wizard dished out even more cruel and unusual punishments to their foes.

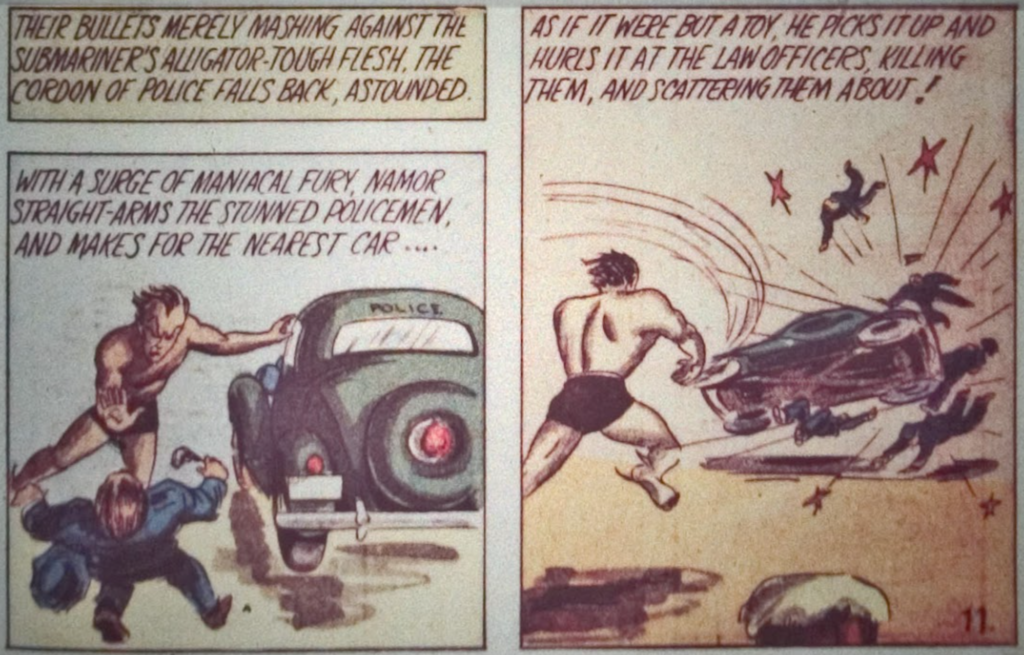

And then there was Namor, the Sub-Mariner. Namor eventually evolved into a more mainstream superhero but he started out as a straight-up super villain. As Nevins points out, this draws on a long tradition of villain-as-protagonist in the pulps: Fantomas, the Octopus, the Scorpion, Fu Manchu, etc. But it’s a tradition that largely disappeared from North American comic books after the Golden Age (with the exception of Namor’s solo comics and the 1975 Supervillain Team-up) until we saw the rise of the anti-hero in the late Bronze Age and early Dark Age. Most notably, The Punisher began as a Spiderman villain before getting his own solo-stories. In the 1990s, characters like Bane, Carnage, Deathstroke, Evil Ernie, Lady Death, Sabretooth, Venom, and the Violator all starred in solo comics.

Boom and bust

The darkest part of the Dark Age was the near collapse of the comic book industry. Comics distributor Capital City estimated the number of comic stores declined from 10,000 in 1993 to 4,500 by early 1996. A number of factors were blamed, with Marvel’s move to go exclusive with Heroes World distribution now taking the lion’s share. But late shipping book, particularly the expensive and overhyped Deathmate Image/Valiant crossover, which created cash flow problems for retailers, and the perceived bait-and-switch that was the Death and Return of Superman, were other important factors. Marvel had to declare bankruptcy in 1996, and many publishers exited the market by the end of 2000, including Awesome Comics, Broadway Comics, Caliber Press, Comico, Defiant Comics, Eclipse, London Night Studios, and Topps Comics.

The Golden Age had its own boom and bust. Action Comics # 1 swiftly sold through its initial print run of 200,000 copies, leading many companies to jump on both the comic book and superhero bandwagons. Magazine publisher Timely Publications launched Marvel Comics # 1 to cash in on the trend, with an initial print run of 80,000 copies that ballooned to 800,000 copies for the second run. Moulton claimed that 18 million comic books were sold per month in 1943. (I wonder whether some of the numbers were fabricated as a way to launder money, more specifically to launder profits made from printing and distributing then-illegal pornography. But maybe I’ve just read too much James Ellroy.)

Interest in superhero comics steadily collapsed in the years following World War II. Publishers pivoted to other genres. Romance, western, and war were popular categories, but it was the crime and horror genres that sparked the moral panic that led to Congressional hearings and transformed the entire industry. Many publishers either folded or sold off their assets in the post-War period, including Fawcett Comics, Fox Feature Syndicate, Fiction House, Lev Gleason Publications, and Quality Comics. EC cut their entire line down to the magazine format MAD.

All of this has happened before, and it will all happen again

I’ve mentioned before that the current era echoes the Golden and Dark Ages. But it’s not happening linearly. It feels like everything is happening at once: a simultaneous boom and bust. Comics sales are doing great, but the implosion of Diamond Distributors is creating strife for the industry, creating darker vibes than we might expect given the health of sales.

The late 2010s and 2020s have seen a lot of new publishers join an already crowded field, including Ahoy, AWA, Bad Egg, Bad Idea, Clover Press, DSTLRY, Ghost Machine, Ignition Press, Ninth Circle, Tiny Onion, and TKO—not to mention the launch of DC’s Absolute line and the Energon line at Image/Skybound. Meanwhile, the blind bag trend could be creating a new speculator bubble. Censors are at the gates.

As John pointed out in our introduction to the Dark Age episode, the comics market and the stories are cyclical. Every so often, publishers decide to take a chance on something new: Maybe a new direction for a struggling title. Maybe a new artist with an unusual style. Or maybe a big-name creator with some sway wants to try something different. New trends emerge and spread, and before you know it, the whole industry is transformed. Then what was once new becomes cliché, and everything starts reverting back to a safe status quo. For various reasons, the stable state tends to generally be the Silver Age versions of the characters. That’s made people think of the roots of superhero comics as shiny and wholesome. But the real roots are dark and messy.